Sometimes, the eye screams in redness and pain. But at other times, it remains outwardly calm while danger brews within. Posterior scleritis is one such silent thief of sight. Though it hides behind the retina, beyond the view of a standard eye exam, its impact can be devastating. Recognizing it early is crucial, not only to save vision but also to uncover potential systemic autoimmune conditions that may lie beneath.

What Is Posterior Scleritis?

Posterior scleritis is a rare, vision-threatening inflammation of the sclera—the white outer coat of the eye—that occurs behind the equator of the globe, affecting the deeper, posterior segment. Unlike anterior scleritis, which is visible and often painful, posterior scleritis may present without redness or obvious external signs, making it harder to diagnose.

It is primarily non-infectious and often driven by an autoimmune process, where the body’s immune system mistakenly attacks its own tissues. This inflammatory reaction is typically mediated by immune complex deposition (Type III hypersensitivity) or vasculitis.

Differential Diagnoses of Conjunctival Masses

Clinical Presentation

The hallmark presenting symptom of posterior scleritis is moderate to severe pain. Patients will often describe a deep, dull, boring pain that, classically, wakes them from sleep. There may be associated pain with extraocular motility, proptosis or other orbital signs. The degree of effect on vision can be variable, from minimally affected to significant vision loss. Intraocular pressure may be elevated in up to half of patients with scleritis, which may be due to rotation of the ciliary body and iris root into the angle causing angle closure without pupillary block, blockage of the outflow track due to inflammation, elevated episcleral venous pressure, peripheral anterior synechiae or neovascularization.

Deep redness and tenderness to palpation due to anterior scleritis also may or may not be present in cases of posterior scleritis. On physical examination, it’s important to lift the eyelids and ask the patient to look in all directions of gaze, as subtle anterior scleritis may not be immediately evident. Patients with strictly posterior scleritis may not have ocular redness but will describe discomfort with motility and may show restriction of eye movement.

Slit lamp biomicroscopy may demonstrate corneal edema, shallowing of the anterior chamber with anterior bowing of the iris and mild to moderate anterior chamber cell.

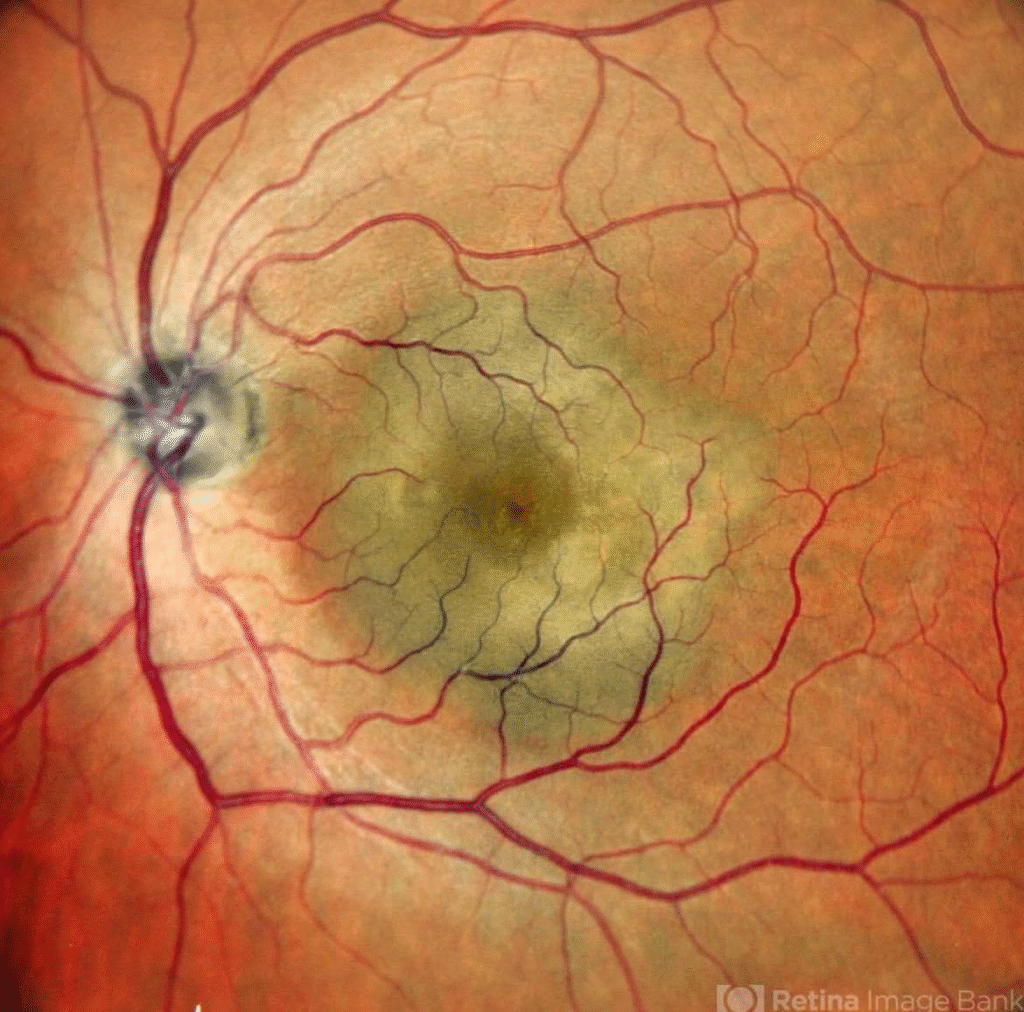

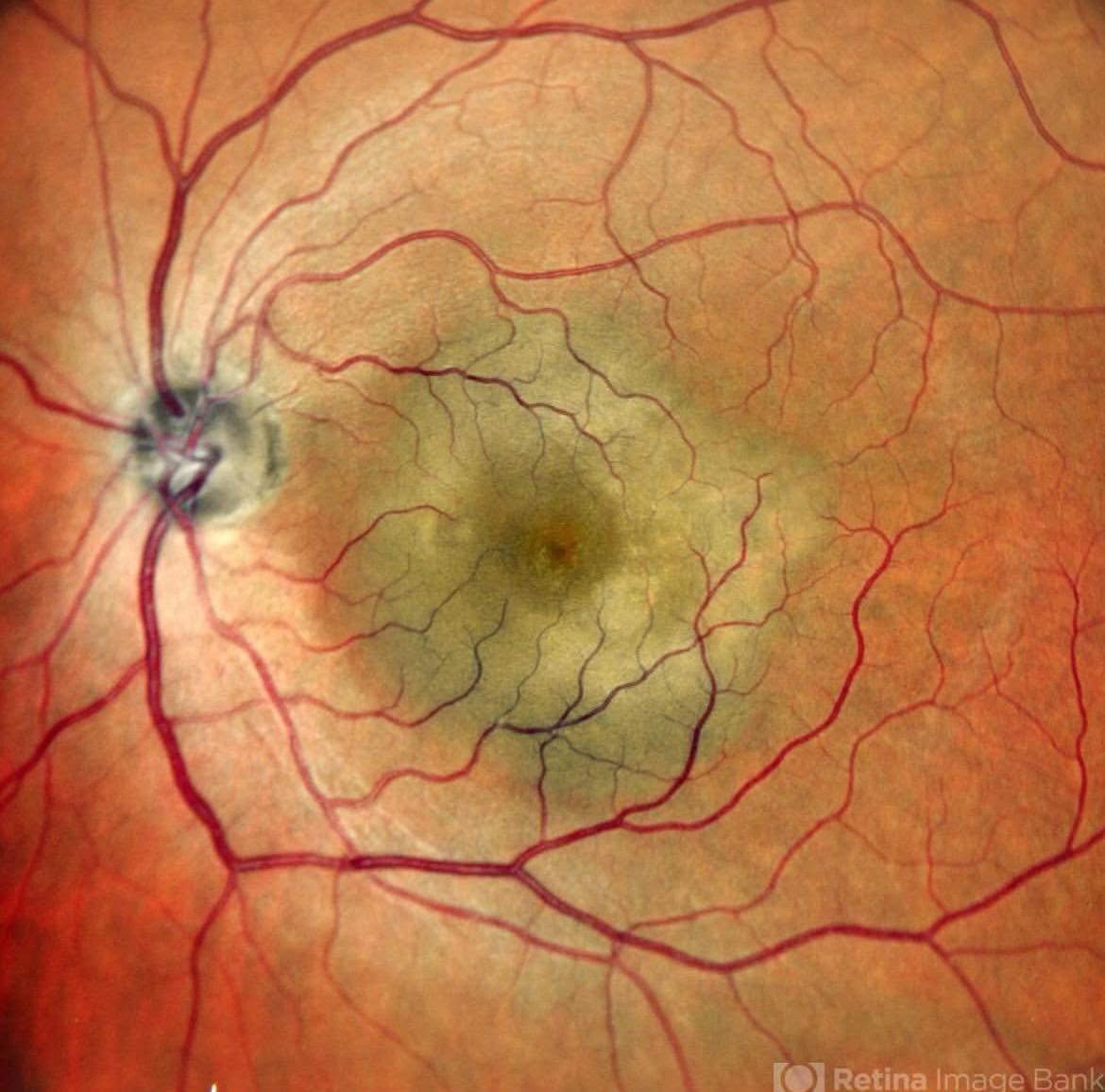

Fundus examination may show swelling of the optic nerve, exudative retinal detachment or choroidal effusions.

Pathogenesis: How It Happens

The inflammation in posterior scleritis is driven by a complex interplay of immune mediators:

- Cytokines like TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β promote inflammation, activate scleral fibroblasts, and attract immune cells to the site.

- Complement proteins C3a and C5a increase vascular permeability, worsening inflammation.

- Matrix Metalloproteinases (MMP-2 and MMP-9) break down collagen in the sclera, leading to thinning and structural changes.

The condition often accompanies systemic autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, or granulomatosis with polyangiitis.

A Clinical Case in Focus

A 49-year-old woman presents with five days of painless blurred vision in the left eye. On examination, her visual acuity is reduced to finger counting at 2 meters. Fundus imaging shows macular elevation with indistinct margins.

This presentation can easily mislead even seasoned clinicians, as it resembles:

- Choroidal tumors

- Exudative retinal detachment

- Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease

Diagnosing the Hidden Culprit

Because posterior scleritis can mimic other conditions, a multimodal diagnostic approach is essential:

- B-scan ultrasonography: The gold standard; look for the classic “T-sign”, indicating fluid in the sub-Tenon’s space.

- Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT): Reveals subretinal fluid, altered foveal contour, and sometimes bacillary layer detachment.

- Fluorescein angiography (FA) and Indocyanine Green Angiography (ICGA): Help rule out choroidal neovascular membranes or other mimickers.

- Laboratory tests: ESR, CRP, ANA, RF, and ANCA should be ordered to screen for systemic autoimmune conditions.

Always ask about systemic symptoms such as joint pain, rashes, or sinus issues—they often provide vital clues.

Management: Aiming to Preserve Vision

The primary goal in managing posterior scleritis is to stop inflammation swiftly and prevent vision loss.

- Systemic corticosteroids: Oral prednisone (1–1.5 mg/kg/day) is often the first line of treatment.

- Intravenous methylprednisolone: Used in severe or vision-threatening cases.

- Immunosuppressants: Agents like methotrexate or azathioprine are introduced when long-term control or steroid-sparing therapy is needed.

- Biologics (e.g., anti-TNF agents): Offer hope in refractory cases and are increasingly being explored.

Treatment should be tailored to the underlying cause, especially when systemic autoimmune disease is present.

A Deeper Reflection

The sclera is avascular, yet in posterior scleritis, it reacts intensely to the whispers of an immune system in turmoil. There may be no redness, no pain, and no outward alarm—but behind the retina, the storm rages. It’s a profound reminder that inflammation doesn’t always announce itself loudly. Sometimes, it hides—in silence, behind the macula, slowly stealing sight.

For clinicians, patients, and caregivers, this reinforces the need for vigilance. Vision loss isn’t always dramatic; sometimes it’s subtle, creeping, and painless. But with awareness, timely diagnosis, and aggressive treatment, posterior scleritis doesn’t have to win.

Follow us in Facebook

Discover more from An Eye Care Blog

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

You must be logged in to post a comment.